From an academic and historical perspective, the Jewish genocide is one of the rare events in modern history where written testimonies are still the main source of information. Photographs, film, and museums about the Holocaust exist without doubt – and in great number today. And yet, the continued proliferation of visual information and tangible artefacts only seems to add more to an abundant body of incoherent and fragmented pieces of history, circling around an elusive and invisible center. I suppose another way of formulating it would be to ask ourselves: are we today closer to a more accurate understanding of the Holocaust?

When photographs showing naked Jewish women being rounded up and bodies being burnt surfaced in the aftermath of the Second World War, the French philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman compared their passage from oblivion to public coverage as being “quatre bouts de pellicule arrachés de l’enfer.” [Georges Didi-Huberman, Images malgré tout , Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 2003].Four pieces of film snatched from hell. Do visual sources of information impart a truth no words can? Or does the opposite also hold true: mediated by choice of words and turns of phrases, do written testimonies offer a better and more adapted paradigm precisely in order to understand a human tragedy? In short, just how far can artistic licence go in helping us come to terms with the industrialised and rationalised mass murder of over 7 million people? And perhaps more importantly, how do we ensure that future generations take something away and ‘learn from’ the Holocaust?

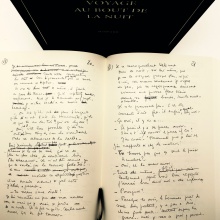

In this article, I shall discuss some of these questions through a comparison of a piece of written and film testimony. The two works are Robert Antelme’s L’espèce humaine and Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah.

Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it. In the case of the Holocaust, remembering the past may be a more complicated question than it first appears to be. This is because concentration camps have literally become institutionalised. With explanatory plaques, glass cases of victims’ personal belongings and audio guides, a visit to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum becomes at once a pedagogical and informative experience, making it ‘easy’ for anyone taking the slightest interest in the subject to learn about the Holocaust. But have we learned from it?

‘Learning about’ is the passive, factual grasping of how the actions of A ramify B. It is a ‘do-this-get-that’ forward-thinking mindset. On the other hand, ‘learning from’ is the looking-backward attempt at reasoning why B is a consequence of A. To ‘learn from’ the Holocaust is therefore to understand why it happened. The apprehension of such knowledge is at once perennial and ethically bound to assure that history never repeats itself. Unfortunately, this linear schematisation of understanding may not be applicable to the absence of the ‘why’ – the unimaginable, senseless horror – of the concentration camps. Indeed, successive perpetrations such as the Rwandan and the Bosnian genocide indicate that our understanding of the Holocaust is limited at best. How are we to obey the ethical imperative of never forgetting that which we do not fully understand? How are we to fully understand that which we cannot write as knowledge?

This article will draw upon Judith Butler’s notion of frames of knowledge precisely to help frame the underlying problems and to define the nature of this conundrum. This will then lead to a discussion of how two works have engaged with this conundrum, revealing an aspect of “horror” in each work not present in the others. Because transmission of trauma also implies active reception on the part of the reader, we will also describe how we, as the reader/viewer, in turn actively engage with the works.

In her book Frames of War[1], Butler argues that knowledge is neither absolute nor discursive, but societal. It is defined only in relation to another frame of knowledge that we ourselves have constructed. This presents a major problem for testimonies of first-generation Holocaust survivors.

In the urgent need to liberate, to alleviate oneself of the burdens of trauma, testimonies produced in the immediate aftermath of the events suffer from a lack of historical objectivity. Psychologist Dori Laub corroborates this observation, asserting that testimonies are only possible retrospectively, for they “[entail] such an outstanding measure of awareness and comprehension of the event – of its dimensions, consequences, and above all, of its radical otherness to all known frames of reference – that it [is] beyond the limits of human ability (and willingness) to grasp, to transmit, or to imagine[2]”. Indeed, as an event “taken at once as paradigmatic of the human potential for evil and as a truly singular expression of that potential which frustrates and ought to forbid all comparison with other events[3]”, how is the full extent of the Holocaust to be understood if there is no other event in history, no frame of knowledge, with which to compare this “radical otherness” – this notion of “horror”?

Primo Levi ripped off the proverbial bandage in affirming that “general significance”, or a shared and commonly accepted understanding of the Holocaust, is unattainable. Instead, the very “significance” of the events is always framed in relation to what writers and artists, as well as readers and viewers, personally regard as being significant. Herein lies the conundrum: it is only through a subjective frame, according to Levi, that objective historical veracity and the collective responsibility to never forget the former are mediated.

However, in the context of the Holocaust, subjective framing of testimonies is problematic. In Chare’s article The Gap in Context, the author argues that the imposed negation of the Muselmann makes it impossible to bear witness to the realities of the Holocaust. Because the subject of the testimony remains in a liminal state, between frames of life and death, the human and inhuman, the object of his testimony will consequently remain between frames, not inside them. This is problematic, for “if […] the only way to bear witness is to return to a fuller selfhood, a return that is enabled by the occurrence of that testimony […] then a central aspect of the camp experience – the loss of self – is lost in the account[4]”. In other words, the recovery of the subjective frame results in the loss of complete historical objectivity; on the other hand, left unsaid, traumatic experiences remain in a state of potentiality, undefined and inapprehensible. Like the figure of the Muselmann, horror is the “in-between, the ambiguous, the composite[5]”, a chimera oscillating between positions. What this means is that horror is not fully transmissible, and can only be partially understood at the expense of something else which lies outside the subjective frame.

The two works to be discussed offer an interesting comparison in their different conception and treatment of horror. In Robert Antelme’s L’espèce humaine, horror is conceived as ”obscurité, manque absolu de repère, solitude, oppression incessante, anéantissement lent[6]”. Because Antelme recounts his personal experiences in the work camps as opposed to the extermination camps, his conception of horror is the endless regress, withering, of the human project – neither human nor inhuman, neither living nor dead. In contrast, Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah is about the extermination camps. Here, horror is not conceived as the anéantissement lent of the human, it is about the néant. Lanzmann concisely summarises his nine-hour project as “a film about the dead and not at all about survival[7]”. This distinction between work and extermination camps must be emphasised, for it affects the nature of the testimony in question. The possibility of “surviving” means the possibility of bearing witness, of a subjective frame.

Clearly, this has influenced Antelme’s use of a subjective frame to stake a universal claim for the human species. In order to construct this subjective frame, Antelme resorts to “choice”, to the use of imagination, in the face of the unimaginable. This choice is as much his’, as writer, as it is the reader’s, to suspend their disbelief, to disengage with the “nécessaire incrédulité[8]”, in order to create a space of necessary imaginative engagement that may allow us to know something. An example of how the reader must actively engage with the testimony in order to ‘know’ something is a scene in the second part of the book, La Route. In this scene, the copains, along with the Nazis, are fleeing the approaching Allied forces. In an effort to reduce the size of the ‘herd’, a SS officer ‘fishes out’ at random one of the numerous filing prisoners – an Italian:

“On a vu la mort sur l’Italien. Il est devenu rose après que le SS lui a dit : Du komme hier ! Il a dû regarder autour de lui avant de rosir, mais c’était lui qui était désigné, et quand il n’a plus douté il est devenu rose. Le SS qui cherchait un homme, n’importe lequel, pour faire mourir, l’avait “trouvé” lui. Et lorsqu’il l’a eu trouvé, il s’en est tenu là, il ne s’est pas demandé : pourquoi lui et plus un autre ? Et l’Italien, quand il a eu compris qu’il s’agissait bien de lui, a lui-même accepté ce hasard, ne s’est pas demandé : pourquoi moi plus qu’un autre ?[9]”

It is important to note that in this instance, the testimony of the Italian’s initial disbelief of having been chosen to die functions precisely through Antelme’s suspension of this very same disbelief. This is apparent in Antelme’s neutral tone – it almost seems that he is not only suspending disbelief, but also refusing to disbelieve, refusing to give into this necessary incredulity – refusing trauma. This is in contradiction with the circumstances under which the book was conceived. Published in 1947 to little acclaim, L’espèce humaine is the product of a “véritable hémorragie d’expression[10]” of the post-war era and of the need to react to, and exorcise, the horror of the concentration camps. Nevertheless, Antelme plays the devil’s advocate, allowing something almost poignant to transpire out of this disaster: “quelque chose de plus haut et de plus fier que le reproche : quelque chose comme une assez hautaine constatation[11]”. When the Italian turns pink, Antelme is not denoting (i.e. – interpreting for the reader) but connoting (i.e. – leaves it to the reader to interpret) the double significance of “il est devenu rose”. The reader must therefore actively engage with the text in order to realise that the Italian could either be turning pink, or becoming the colour pink itself.

In a way, Antelme succeeds where many have failed: he draws upon imagination to create a space of projection within which the reader ‘inserts’ himself to witness, as Antelme himself has witnessed, the “framing out” of the Italian from normative instances of life, allowing us to see something of the spectral figure of the Muselmann. Judith Butler writes: “there is no life and death without a relation to some frame[12]”. Through the use of a subjective frame, Antelme frames out the Italian from himself and the others who continue marching, casting him out of what is considered a normative definition of life, and making apparent the disappearing symbolic potential of the face as it becomes pink. Through this relativisation of human life, Antelme allows us to know something about the criteria against which the Nazis judged those who were or weren’t worthy of living.

So has Antelme successfully engaged with this conundrum? Indeed, through imagination, Antelme creates a metonymic representation of the Muselmann – the impossible witness – to whom he bore witness. While this can never fully represent the original experience, for there will always be a gap between witness and testimony, Antelme, far from reconstituting what he saw, constitutes something beyond the directly verifiable – something of this sense of shame of the Italian at his complicity in his own meaningless death. In his article The Rhetoric of Disaster, Bernard-Donals writes: “What the Holocaust shows, perhaps more clearly than other traumatic events, is that discourse cannot represent what has been seen, and that at best it indicates the effect upon the witness of what [he] saw[13]”. Indeed, it is through ‘unwriting’ – “non pas un langage et une écriture retrouvés intacts après l’épreuve, mais traversés par cette épreuve même[14]” – that the reader can begin to conceive not so much a full understanding of horror as an understanding of the traumatic effects of horror on Antelme.

On the other hand, Lanzmann’s Shoah is not subjectively framed in that it does not focus on a single personal story with a linear narrative. Instead, the structure of the film is circular: “images and words circle obsessively around the sites of destruction, moving ever closer to an elusive center[15]”. As the title suggests, Shoah is an encyclopaedic project that attempts to define the Holocaust as a totalising event via selected testimonies. While the content of the testimonies are revealing, our focus should instead be the method Lanzmann employs to create a unique documentary within the Holocaust filmic corpus. Insdorf writes: “The achievement of Shoah is that it contains no music, no voice-over narration, no self-conscious camera work, no stock images – just precise questions and answers, evocative places and faces, and horror recollected in tranquillity[16]”. Through Shoah, Lanzmann creates a “new form” of testimony, one that refrains from any use of historical, archival footage in favour of present, ‘live’ testimonies. This, Lanzmann claims, leads to the “création de la mémoire[17]” of the events.

In one of the later scenes, Lanzmann interviews Abraham Bomba, a Polish-Jewish survivor of Treblinka who was forced to cut the hair of women before they were sent to the gas chambers. The interview takes place in a barbershop in Israel. This mise-en-scène is the tool to the creation of memory, precisely because it makes use of the present time and place to reactivate memories of the past. Lanzmann pushes it further by asking Abraham to re-enact the way he cut women’s hair. By subjecting Abraham to this re-enactment, the witness is not only reactivating, but also reliving, memories of the camps. And then, Lanzmann pushes it further, asking Abraham to answer a question he has been avoiding:

Lanzmann: But I asked you and you didn’t answer: What was your impression the first time you saw these naked women arriving with children? What did you feel?

Bomba: […] A friend of mine worked as a barber – he was a good barber in my hometown – when his wife and his sister came into the gas chamber . . .

Lanzmann: Go on, Abe. You must go on. You have to.

Bomba: I can’t. It’s too horrible. Please.

Lanzmann: We have to do it. You know it […][18]

It is moments like these which impart a truth about the Holocaust. It is not only what the witness says, but also how he says it, the look in his eyes, the trembling of his lips, which reveals something about the horror no words can. Indeed, written testimonies such as Antelme’s are more subjective, for they are guided by certain choices of words and turns of phrases. Similarly, Lanzmann’s selected live testimonies may be considered subjective, for they were selected. Nevertheless, live testimonies possess a degree of unpredictability that written testimonies unfortunately do not, for the film camera not only records the words of the witness, but also his body language.

All this being said, for someone who is as experimental in his approach to documentary filming, it comes as a surprise that Lanzmann claims Shoah to be the ‘purest’ form. By doing so, Lanzmann ironically creates a normative frame against which all other modes of representation of the Holocaust are judged and negated. Moreover, this goes against the very objective of the film: the reckoning with the impossibility of representation. Would Antelme’s L’espèce humaine be worth any less because it attempts to represent the Holocaust through a subjective frame? Instead, it is preferable to view each work as complementing each other. As a piece of reactive testimony, L’espèce humaine’s prerogative is to use imagination to “faire passer une parcelle de vérité[19]” through a mediated and metonymic mode of representation, in order to ‘take leave’ of trauma. Shoah, on the other hand, does not deal with the “convoluted logic of dehumanisation that characterised the Final Solution[20]” as much as prompting us to never forget the Holocaust – or rather, that it can never be forgotten, for it never ends and is constantly relived in the present.

Is it possible to find a compromise between the two parts to this conundrum after all? That the extent and horror of the Holocaust can never be fully understood is confirmed in both of the works discussed. In Robert Antelme’s L’espèce humaine, the use of a subjective frame inevitably frames out the loss of subjectivity – an important defining feature of the horror of the camps. This is a paradox that will never be solved. Nevertheless, this same subjective frame, by its very relation to that which it casts out, also allows us to know how one man may be defined in relation to another, but also that ultimately, we are all part of “unité indivisible[21]” of the human species. In Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, it is affirmed from the outset that it is impossible to represent, let alone fully understand, the Holocaust. However, through the use of live testimony and the abstention from all historical footage, Lanzmann shows that even traumatic, repressed memories can be relived in the absence of traces. It never ends.

In both cases, Antelme and Lanzmann have at the very least fulfilled the demand that the realities of the concentration camps never be forgotten, for their works have had an important impact on posterity and have inspired other writers and artists, as well as researchers and students, to keep learning about – and more importantly – to keep learning from the Holocaust. Perhaps the very reason that subsequent atrocities continue to transpire today is due to insufficient historical hindsight that has not yet provided us with a frame of knowledge to better understand this radical otherness of the Holocaust. Perhaps with time, through this movement between the ‘approaching toward’ and the ‘taking leave of’ trauma, will memory of the Holocaust evolve, and an indelible mark will impart upon the conscience of men.

···

— C.S.

Footnotes

[1] Judith Butler, ‘Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?’, (New York, 2009)

[2] Nicholas Chare, ‘The Gap in Context: Giorgio Agamben’s Remnants of Auschwitz’, Cultural Critique, 64 (Fall 2006), p.41

[3] Michael Rothberg, ‘We Were Talking Jewish: Art Spiegelman’s Maus as Holocaust Production’, Contemporary Literature, Vol.35, No.4 (Winter, 1994), p.670

[4] Chare, p.58

[5] Julia Kristeva,’ Powers of Horror’, Trans. Leon S Roudiez (Columbia University Press, 1982), p.4

[6] Robert Antelme, ‘L’espèce humaine’ (Gallimard, 1957), p.11

[7] Claude Lanzmann, ‘Lanzmann on Schindler’s List’, http://phil.uu.nl/staff/rob/2007/hum291/lanzmannschindler.shtml, [accessed on 24/03/2014]

[8] Antelme, p.302

[9] Antelme, pp.241-2

[10] Thomas Regnier, ‘L’unité indivisible de l’humanité’, Le Magazine Littéraire, N°438, (January 2005), p.50

[11] Francis Ponge, ‘Note sur « Les Otages », Peintures de Fautrier, Tome Premier (Gallimard, 1965), p.450

[12] Butler, p.7

[13] Michael Bernard-Donals, ‘The Rhetoric of Disaster and the Imperative of Writing’, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Vol.31, No.1 (Winter, 2001), p.87

[14] François Bizet, ‘Postérité de L’Espèce humaine’, French Forum, Vol.33, No.3 (Fall 2008), p.58

[15] Toby Haggith and Joanna Newman, ‘Holocaust and The Moving Image : representations in film and television since 1933’, (Wallflower Press, 2005), p.162

[16] Annette Insdorf, ‘Indelible Shadows : Film and The Holocaust’, (Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 240

[17] Daniel Bougnoux, ‘Le monument contre l’archive : entretien avec Claude Lanzmann’, http://www.mediologie.org/cahiers-de-mediologie/11_transmettre/lanzmann.pdf, p.274 [accessed on 24/03/2014]

[18] Claude Lanzmann, ‘Shoah: The Complete Text of the Acclaimed Holocaust Film’ (First De Capo Press, 1995), p.107

[19] Antelme, p.302

[20] Michael Bernard-Donals and Richard Glejzer, ‘Between Witness and Testimony: The Holocaust and The Limits of Representation’, (State University of New York Press, 2001), p.12

[21] Antelme, p.11

Bibliography

Antelme, Robert. L’espèce humaine. (Gallimard, 1957).

Bernard-Donals, Michael. The Rhetoric of Disaster and the Imperative of Writing. (Rhetoric Society Quarterly, Vol.31, No.1, Winter, 2001).

Bernard-Donals, Michael and Glezjer, Richard. Between Witness and Testimony: The Holocaust and The Limits of Representation. (State University of New York Press, 2001).

Bizet, François. Postérité de L’Espèce humaine. (French Forum, Vol.33, No.3, Fall 2008).

Bougnoux, Daniel. Le monument contre l’archive : entretien avec Claude Lanzmann. http://www.mediologie.org/cahiers-de-mediologie/11_transmettre/lanzmann.pdf. [accessed on 24/03/2014].

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (New York, 2009).

Chare, Nicholas. The Gap in Context: Giorgio Agamben’s Remnants of Auschwitz. (Cultural Critique, 64, Fall 2006).

Haggith, Toby and Newman, Joanna. Holocaust and The Moving Image: representations in film and television since 1933. (Wallflower Press, 2005).

Insdorf, Annette. Indelible Shadows : Film and The Holocaust. (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror. Trans. Leon S Roudiez (Columbia University Press, 1982).

Lanzmann, Claude. Shoah: The Complete Text of the Acclaimed Holocaust Film. (First De Capo Press, 1995).

Lanzmann, Claude. Lanzmann on Schindler’s List, http://phil.uu.nl/staff/rob/2007/hum291/lanzmannschindler.shtml, [accessed on 24/03/2014].

Ponge, Francis. Peintures de Fautrier. Tome Premier (Gallimard, 1965).

Regnier, Thomas. L’unité indivisible de l’humanité, Le Magazine Littéraire. N°438, (January 2005).

Rothberg, Michael. We Were Talking Jewish: Art Spiegelman’s Maus as Holocaust Production. (Contemporary Literature, Vol.35, No.4, Winter, 1994).