I have lived in many countries throughout my life, but nowhere else can I find cinemas as lavish and as self-sustaining as the ones in Thailand. Going to the cinema no longer conjures up images of young couples going on a date, making out, with popcorn on their laps and a giant Coca-Cola in the cup holder. These days, going to the cinema is no longer just about watching good (and bad) movies. It is about selling, and paying through your nose, for reclining chairs and attentive concierge service, access to a wifi hotspot with a fully-stocked bar. Going to the movies is a fully-fledged lifestyle concept.

In an increasingly globalised society where business and pleasure are becoming increasingly intertwined, cinemas are finding it increasingly essential to align commercial interests with their customers’ personal needs. These factors contribute to the function and influence the way in which cinemas are designed to follow the current technological and social trends. Design, in this case, may be defined spatially and architecturally. More importantly, Design with a capital ‘d’ is never absolute. It is always relative to how the created space is used, or put simply, how form and function articulate. But technology sooner or later becomes obsolete, and social trends change with time, leaving the function and form of the cinema to be reinterpreted in a new way. In this article, I will compare the Paragon Cineplex and the Scala, examining a cinema following a current design trend and one that has been reinterpreted.

The Scala was originally built in 1967 reflecting post-war optimism in the US and promoting the “quality time” culture. At a time when going out was always a treat, cinemas were deeply appreciated as a means for one to spend quality time with the family, and so “going to the movies was a major event and you felt like being welcomed by the film director in person[1]”. But the onslaught of globalization starting in the late 1980s brought with it an insatiable appetite for money and an opportunity to urbanize both cities and people so as to divert their attention from such cinemas to larger venues for shopping, dining, and a new breed of cinemas fostered by the corporate oligopoly, one of which is the Paragon Cineplex. Unlike the Paragon Cineplex, the Scala’s design function is less commercial and more sentimental. Certain design cues once considered contemporary have now become mere skeuomorphs – that is to say, design features once considered functional, or at least, as functional as technology would allow in those days, have become ornamental. From glass-cased ticket booths with brass cashier machines to the hand-painted film posters, a trip to the Scala takes you back to the good old days.

Opposite from Siam Square, the Paragon Cineplex makes an impressive statement in favour of modern mass consumerism. Both cinemas are ample in size, but the way in which space is manipulated and the number of screening rooms in each is different. The design of the lobby in the Paragon Cineplex assumes the role of the usher, leading moviegoers into the 14 screening rooms by separate corridors. The lobby therefore becomes a “transitional point, like an airport, where people are continually arriving and leaving, each with a different agenda. [2]” Ushers at Scala, however, preserve the tradition of escorting viewers to their seats in any of its three theatres, and so the grandeur of the space is emphasized, creating a sense of community where “everyone there [is] sharing the moment…[and] the emotion, excitement, inspiration, or heartbreak just witnessed[3].”

Fig.1 The grand foyer at the Paragon Cineplex. Note that the spatial dimensions of the two cinemas are similar, but the foyer acts as a large crossing, leading moviegoers into different corridors and chambers.

Despite these differences, both cinemas are in a united front against home television. As people go to cinemas precisely for the things their television sets cannot offer, cinemas have to offer a unique selling point to stay in operation. In this regard, the Paragon Cineplex goes to great lengths to offer digital screening and simulated three-dimensional IMAX films, Scala merely offers large projection screens and stereophonic sound. In the era of sharp high-definition plasma televisions that exceed the image quality of theatre projections, Scala would seem to be falling behind – and this is undeniably true. But what globalization has done to subjugate Scala has only preserved its legacy better, and so technology becomes secondary to the function and design that has been reinterpreted.

What was once trendy is now timeless, and this obstinacy against the changing tides of time is the very reason architectural charm sells at Scala while Paragon’s sales are driven by the spending of big money on cinematic technology that would keep it a par ahead of average home televisions. Scala’s neoclassical interior such as the heavy red curtains, Greco-roman columns, vaulted ceiling, the grand staircase and marble floor in the reception hall reflect the grandeur of 19th century opera houses, conjuring up images of women in white satin gloves being escorted by men in tuxedos up the grand staircase. Paragon’s modern design, on the other hand, serves well the corporate “fast-food approach to cinemas[4]” because mainstream audiences only look to enjoy what 21st technology can do to enhance viewing experience. Technology is therefore a more important factor and every branch seems to be a replica of the other. In this way, Scala is unique and stands out from such “theatres [that are] named for the shopping mall that swallowed them up[5]”, pointing to the change in social trend and people’s lifestyle from domestic suburbanites who go to cinemas to spend time with their loved ones to out-going urbanites who make it a weekly routine in addition to shopping and dining.

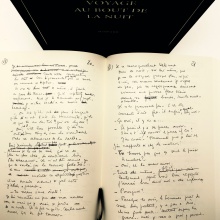

Fig.2 The double staircase leading to the Scala cinema.

As the architectural design of the two cinemas is different, the same will apply for how things are run. At Scala it is all manual labour – from bookkeeping to the marquee displaying show times, moviegoers are further charmed by the character factor, and so convenience is not an issue. But this is an issue for Paragon because inconvenience means less advertising and exposure. Since moviegoers come here not for the movie-going experience but for the movie itself, heavy investment is made on increasing screening rounds and digitalizing booking systems to reduce queues, as well as screens and sound systems, all to maximize audience reception of commercials. In contrast to Scala’s “simple tradition of showing good movies[6]”– which do not always vary on budget and cast – Hollywood films are often Paragon’s predominant screening selections since profit can be made from the sale of product tie-ins of these blockbusters.

And so from this it is clear that while the design of both the Scala and the Paragon Cineplex are determined by its architects, cinema owners and customers, these people merely influence what it is built for and how. Time, however, plays a greater role in the interpretation and reinterpretation of the two design principles because as social reaction to design changes over time, what we see as trendy today could be fossil or classic ten years from now. The most important distinction that can be made between the two cinemas is that Scala was once a reflection of our perception of cinema just as the Paragon Cineplex is perceived now. But the passing of time has since altered that perception and now it is a memento of the bygone days.

— C.S.

Footnotes

[1] The Scala’s Old Cinema Glamour (internet article)

[2] Maggie Valentine, An Architectural History of the Movie Theatre, p.188

[3] Maggie Valentine, An Architectural History of the Movie Theatre, p.184

[4] Maggie Valentine, An Architectural History of the Movie Theatre, p.188

[5] Maggie Valentine, An Architectural History of the Movie Theatre, p.182

[6] The Scala’s Old Cinema Glamour (internet article)

Bibliography

The Scala’s Old Cinema Glamour (internet article) – http://absolutelybangkok.com/the-scalas-old-cinema-glamour/

Valentine, Maggie. The Show Stars on the Sidewalk – An Architectural History of the Movie Theatre. Yale University Press, New Haven and London. 1994.