In the summer of 2013, I took a plane from Paris back to Bangkok. I was longing for home. I figured a little time spent away from my hometown would allow me to put two distinct cultures and cities into perspective. Tabula rasa as they say. For the first time, I visited the main tourist attractions. I was among tourists and for the first few days, I definitely felt like I was fitting in. A street vendor took me for a Korean tourist, and for a brief moment I was happy to play the part. I also felt it was necessary if I was to see Bangkok in a different way. And so began an investigation…

What makes Bangkok the city it is today? Why do foreigners (and perhaps Thais also) say that Bangkok is “the city of angels”? Generally speaking, how do most of the world’s major cities remain distinctive and resist the homogenising effects of today’s globalised economy? In short, what gives a city its unique characteristic, its ‘staying power’?

One way of answering the question is indeed to look at it from an outsider’s perspective, removing one’s self from the city, and taking the city at face value. The world’s major cities are instantly recognisable because they can be reduced to a visual metonym. The Eiffel Tower, the Sydney Opera House, and the Statue of Liberty are three examples of timeless urban égéries. They are the product of a three-step intergenerational process: first, as objects we can touch and contemplate, second, as prototypes of mass reproduction and third, as indisputable canons of modern art and culture. Underlying this process of canonisation, the twentieth-century German thinker Walter Benjamin argues that art objects possess a special, temporal “aura” that can only be felt and perceived at the time of its creation. As we proliferate, preserve and restore these objects to their original state, their original aura wears off. Later, the French philosopher Guy Debord declared, “all that was once directly lived has become mere representation.”

Benjamin and Debord each witnessed a different stage of capitalism, but both were essentially Marxist thinkers. Fascinated with the Parisian arcades of the 1830s and 1840s, Benjamin saw in these arcades a paradigm of modernity. Where most commercial spaces were out in the open, arcades brought them ‘inside’. Made of glass and steel, arcades challenged the notion of the interior and the exterior, breaching boundaries between the two spaces, bringing the light of day into a space conventionally built outside. The arcades were simultaneously inside and outside spaces. At the same time, window dressing was becoming a fully-fledged art, preventing people from touching objects, and transforming these objects into fetish, objets fantasmagoriques. No longer tactile, something of the intrinsic, ‘true’ value of the object is lost. Instead, now the object may only be understood in relation to one’s purchasing power, and the ability to own it. As Debord claims, “l’homme est passé de l’être à l’avoir, puis de l’avoir au paraître.” From being to having, and from having to appearing to be, modern capitalism has come full circle.

Bangkok makes for an interesting case study because, despite all the tourist monuments I visited, there is no one monument that can lay claim to a single, metonymic representation of the city that everyone instantly recognises. This is nothing unusual. Many cities around the world do not have their very own Eiffel Tower. And yet, there is something to be said about a city that is home to hundreds of shopping malls, and not just any kind of shopping malls. When EmQuartier opened its doors to the public in March 2015, people had seen nothing quite like it – a self-sustained universe, not only of shops, restaurants and other standard amenities, but also a hanging garden much like the ancient city of Babylon, overlooking the smaller, ancestral Emporium mall. The owner plans to inaugurate yet another shopping complex in a few years, aptly named the EmDistrict.

“Quartier”…“district”…composites of conventional urban space, built as a shrine to mass consumerism. Bangkok is indeed at a critical juncture in urban history, and its urban policies must reflect a willingness to preserve historically important architectural structures and monuments. It is a fallacy to believe that creating modern, commercial infrastructures would sustain a growing economy in the long run. It is also a fallacy to believe that only certain things and objects adhering to certain socioeconomic criteria may be deemed culturally valuable. Unfortunately, this is how ‘culture’ is most often perceived – as physical and tangible objects, structures fixer-uppers for which we may conveniently draw up appraisals and profit margins.

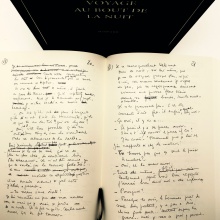

Neither fungible nor liquid, culture is not a commodity. It is intrinsically invaluable, irreplaceable, and does not only appear to be so. I have been told that cities can be read as a palimpsest of things come and gone. Bangkok is no exception to the rule. Take a piece of the city, stand in a corner of a busy intersection, and notice everything going on around you. A small, irreducible piece of the whole.

— C.S.